Unlocking the Next Frontier: An Essential Guide to Quantum Computing

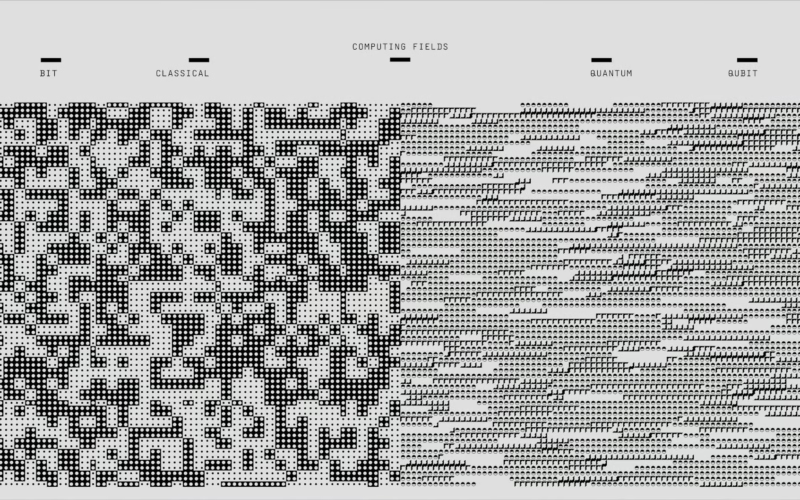

Quantum computing represents the most significant shift in information technology since the invention of the microchip. It is not simply faster classical computing; it is an entirely new paradigm built upon the counterintuitive laws of quantum mechanics—the physics governing the smallest particles in the universe. While classical computers rely on binary bits that must be in one of two states (0 or 1), quantum machines utilize ‘qubits’ capable of existing in multiple states simultaneously. This fundamental difference unlocks computational power capable of tackling problems that would take even the most powerful supercomputers billions of years to solve, fundamentally redefining what is computable and paving the way for revolutionary advancements in fields ranging from medicine and artificial intelligence to materials science and cryptography.

Understanding this technology requires moving beyond traditional physics and embracing concepts that seem almost impossible in our everyday experience. This guide breaks down the core components, the theoretical underpinnings, the practical applications, and the challenges currently facing a field poised to reshape the 21st century.

The Quantum Leap: Demystifying Qubits, Superposition, and Entanglement

The foundation of quantum computing rests on three principles of quantum mechanics: qubits, superposition, and entanglement. These properties allow quantum processors to explore computational spaces exponentially larger than their classical counterparts.

Qubits: The Quantum Bit

A qubit (quantum bit) is the basic unit of information in a quantum computer. Unlike a classical bit, which represents a sure 0 or a sure 1, a qubit can exist as a mix of both states simultaneously. This ability is known as superposition. Think of a classical bit as a light switch that is either on or off; a qubit is like a light dimmer that can be set to any brightness level between fully off and fully on, representing a probability distribution of 0 and 1 until it is measured.

Mathematically, a single qubit can perform two calculations at once, but the power grows exponentially. A system of 50 qubits, if perfectly functional, could represent $2^{50}$ states simultaneously. This number is greater than one quadrillion, illustrating how a modest increase in the number of stable qubits correlates to an astronomical increase in processing capability. The current challenge in the field is creating stable qubits that can maintain these superposed states without collapsing.

Superposition: Computing in Parallel Realities

Superposition is the mechanism that allows quantum computers to execute complex algorithms simultaneously across an entire landscape of possibilities. By placing qubits in superposition, a quantum algorithm can process all potential inputs at once. When the computation is completed, the system collapses into a single, definite outcome—the solution to the problem, guided by the algorithmic structure. This process of collapsing is known as ‘measurement’ and is what yields the final, classical answer.

Entanglement: The Ultimate Connection

Entanglement is arguably the strangest and most powerful resource in quantum computing. When two or more qubits become entangled, they become linked in such a way that they share the same fate, regardless of the physical distance separating them. If one entangled qubit is measured and found to be in the ‘0’ state, its partner instantly adopts a corresponding, correlated state. Einstein famously called this phenomenon “spooky action at a distance.”

Entanglement allows quantum computers to link the processing capacity of multiple qubits into a single, complex quantum state, creating powerful computational shortcuts that have no equivalent in classical physics. Leveraging entanglement is essential for performing advanced quantum operations and for future quantum communication systems.

Building the Machines: Architectural Realities

Building a quantum computer is an immense engineering challenge, primarily because the delicate quantum states required for computation are incredibly sensitive to environmental ‘noise’—heat, vibration, or stray electromagnetic fields.

Competing Hardware Approaches

The field is not dominated by a single technology; several competing physical architectures are being pursued globally by major tech companies and specialized startups:

1. Superconducting Qubits: Used by companies like Google and IBM, these systems rely on circuits made of superconducting materials kept at temperatures near absolute zero (colder than deep space). At these temperatures, the circuits exhibit quantum properties, allowing them to function as qubits. This approach is highly scalable but requires immense cryonic infrastructure.

2. Trapped Ion Qubits: Companies such as IonQ utilize lasers to suspend individual atoms in a vacuum chamber, trapping them with electromagnetic fields. The energy levels of these ions serve as qubits. Trapped ion systems generally boast the highest fidelity (lowest error rates) but are currently limited in the total number of qubits that can be effectively managed.

3. Photonic Qubits: This approach uses photons (particles of light) as the carriers of quantum information. Photonic systems are relatively robust against decoherence but face challenges in storing and manipulating light signals efficiently.

4. Topological Qubits: A theoretical approach heavily researched by Microsoft, topological qubits aim to encode information in the structural arrangement of particles, making them inherently more resistant to local noise and environmental interference. While promising, this technology remains largely theoretical and difficult to construct in a lab environment.

The Challenge of Decoherence

The greatest hurdle in scaling up quantum computers is decoherence. Decoherence is the process where a qubit loses its delicate quantum state (superposition or entanglement) and collapses into a classical 0 or 1. This is caused by interaction with the environment. Because computation must occur before coherence is lost, most operational quantum computers must be cooled to fractions of a degree above absolute zero or isolated in high-vacuum environments.

The short coherence times of current qubits mean that calculations must be extremely fast, and the instability necessitates sophisticated and computationally expensive forms of quantum error correction. Estimates suggest that thousands or even millions of physical, noisy qubits may be required to encode a single highly reliable, logical qubit, highlighting why quantum scaling is less about simple fabrication and more about complex control systems.

The Transformative Potential of Quantum Computing

While general-purpose quantum computers with millions of stable qubits are likely decades away, even today’s unstable, “noisy intermediate-scale quantum” (NISQ) devices offer glimpses into revolutionary applications.

Quantum Algorithms

The true power of quantum computing is realized through specific algorithms designed to exploit superposition and entanglement. Two examples stand out:

Shor’s Algorithm: This algorithm can efficiently factor very large numbers. While this sounds abstract, it is the mathematical backbone of modern public-key encryption standards, such as RSA. A large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm could theoretically break much of the current internet encryption infrastructure, making post-quantum cryptography a critical area of research.

Grover’s Algorithm: Designed for unstructured database searching, Grover’s algorithm offers a quadratic speedup over the best possible classical search methods. While classical search requires $N$ steps to find an item in a database of $N$ items, Grover’s requires only $sqrt{N}$ steps, vastly accelerating search and optimization processes.

Revolutionizing Material Science and Drug Discovery

Perhaps the most immediately impactful application is simulating quantum systems. Classical computers struggle immensely when trying to accurately model complex molecules, chemical reactions, or novel materials because the required calculations scale exponentially with the number of electrons involved. To date, pharmaceutical companies use significant approximations to simulate drug interactions.

Quantum computers are inherently designed to simulate quantum systems. They could accurately model complex protein folding, design new catalysts for efficient energy production, or engineer novel superconducting materials, dramatically accelerating the time it takes to develop new medications or sustainable technologies.

Financial Modeling and Artificial Intelligence

In finance, quantum machines could optimize complex portfolios, model systemic risks, and detect sophisticated fraud patterns far more quickly than traditional methods. The ability to handle vast, interconnected optimization problems in real-time could redefine global financial strategies.

Furthermore, quantum machine learning (QML) aims to apply quantum principles to existing AI algorithms. While the field is nascent, there is hope that QML could dramatically accelerate the training of deep neural networks, leading to breakthroughs in areas like image recognition, natural language processing, and advanced industrial automation.

Current Landscape and Future Outlook

Today, quantum computing is primarily accessed via the cloud, allowing researchers, developers, and corporations globally to experiment with real quantum hardware provided by companies like IBM and Google. This democratization has fueled rapid progress and the development of quantum programming languages and software tools.

The timeline for widely adopted, fault-tolerant quantum computing is frequently debated. Most experts agree that we currently inhabit the NISQ era—machines with between 50 and 1,000 noisy qubits that can perform limited but powerful calculations that cannot be simulated on classical computers, offering a “quantum advantage” in niche areas.

The next major milestone beyond NISQ is achieving fault tolerance: the creation of logical qubits that maintain stability against environmental noise. This represents a monumental engineering challenge but, once achieved, will usher in the era of true large-scale quantum applications.

For professionals, students, and businesses, preparing for the quantum future involves strategic investment in education and research. Understanding quantum concepts and the capabilities of NISQ machines today is essential, ensuring that organizations are ready to leverage the technology when it fully matures and moves from the theoretical lab bench to the practical realm of industrial and scientific application. The quantum revolution is not a question of if, but when, and its eventual impact will span every major sector of the global economy.